In the foothills of the Himalayas, approximately 70,000 Tibetans find themselves in a constant struggle for identity while living in exile in India. Tenzin Tsundue, a poignant Tibetan writer and activist, encapsulates this struggle: “When we were in school, our teachers used to say that there is an 'R' on our forehead – meaning refugees.”

Fleeing the oppressive regime of Chinese rule, thousands of Tibetans migrated to India since a failed uprising in 1959. Led by their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, they traversed perilous mountain paths and were granted refuge in India, which offered them a safer haven tied by cultural and religious bonds.

Yet, Mr. Tsundue points out a bitter irony: while they reside in India, they are not considered Indians. Tibetans must rely on renewable registration certificates issued by the Indian government, every five years. Those born within the country can apply for Indian passports only if their parents were born there between 1950 and 1987, thereby compromising their Tibetan identity—a decision many refuse to make.

A poignant reflection emerged during Dalai Lama's 90th birthday celebration in Dharamshala, a town that serves as the base for the Tibetan government-in-exile: while the community came together in celebration, an undercurrent of uncertainty lingered, overshadowed by the strains of their geopolitical situation.

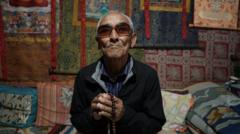

Dawa Sangbo, who trekked from Tibet to India in 1970, recalls living in a tent for twelve years, revealing that while he found safety, a longing for his homeland remains ever-present. "A home is a home," he says wistfully. This profound attachment resonates with another exile, Pasang Gyalpo, who, despite fleeing to India for security, has family still living in Tibet. “What else can I feel but pain?” he reflects.

Younger Tibetans, born in India, express a deeper existential anguish: the feeling of being deprived not only of their homeland but also of their heritage. Lobsang Yangtso, a researcher on Himalayan regions, articulates the sentiment of being stateless: “It’s painful. I have lived all my life here [in India] but I still feel homeless.”

Though grateful for refuge, Tibetans here cannot vote, own property, or easily travel without an Indian passport. Many eye opportunities abroad as the economic allure of Western nations grows increasingly appealing, resulting in a silent exodus toward countries like the US and Canada, using official travel documents accepted by some nations.

However, for individuals like Thupten Wangchuk, leaving isn't just about the pursuit of better economic prospects; it is also about reconnecting with family long left behind. “I haven't met my parents in almost 30 years,” he shares earnestly.

The ongoing tensions with China further complicate their longing to return. The Dalai Lama's recent announcement about his succession sparked concern, with Chinese authorities asserting control over this sensitive topic, which poses challenges to India-Tibet relations.

While the Dalai Lama's presence provides a beacon of hope for many, uncertainties remain vital to the community's future, echoing the fears that the Tibetan movement might flounder without his guidance. "It's thanks to the current Dalai Lama that we have these opportunities," Mr. Phuntsok shared, highlighting concerns that once he passes, those opportunities may dissipate.

As the Tibetan community in India continues to navigate this complicated tapestry of identity, hope, and longing, their story remains a testament to resilience amid the continuing quest for connection to their land and culture.