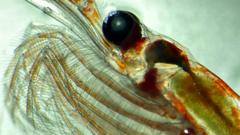

Researchers have uncovered that these small, unsung heroes, known as zooplankton, particularly copepods, engage in a remarkable migratory behavior that aids in locking away substantial amounts of carbon. During spring, these creatures gorge themselves before descending hundreds of meters into the depths of the Southern Ocean, where they metabolize stored fat, ultimately sequestering an estimated 65 million tonnes of carbon each year—equivalent to the annual emissions of around 55 million petrol cars.

Despite their significant contributions to carbon storage, these creatures have historically received little attention compared to more prominent Antarctic species like whales and penguins. Their life cycle is intriguing: zooplankton consume phytoplankton at the ocean's surface and then burn the fat they’ve accumulated when they migrate to deeper waters for the winter. This process, involving the seasonal vertical migration pump, allows for carbon to be stored deep in the ocean, delaying its release into the atmosphere for decades or even centuries.

However, scientists are increasingly concerned about the potential threats to zooplankton populations, such as climate change, warming oceans, and commercial harvesting of krill, which could jeopardize not just their survival but also the critical ecological functions they perform. The findings from this research stress the necessity for further studies and integration of their roles in climate models, as their absence could considerably amplify atmospheric CO2 levels and temperature rises.

As researchers continue to study these fascinating creatures on expeditions aboard specialized research vessels, their work provides hope that understanding and conserving zooplankton will be critical in the fight against climate change. The study's results have been published in the renowned journal Limnology and Oceanography, demonstrating the ongoing importance of marine ecosystems in combating global warming.

Despite their significant contributions to carbon storage, these creatures have historically received little attention compared to more prominent Antarctic species like whales and penguins. Their life cycle is intriguing: zooplankton consume phytoplankton at the ocean's surface and then burn the fat they’ve accumulated when they migrate to deeper waters for the winter. This process, involving the seasonal vertical migration pump, allows for carbon to be stored deep in the ocean, delaying its release into the atmosphere for decades or even centuries.

However, scientists are increasingly concerned about the potential threats to zooplankton populations, such as climate change, warming oceans, and commercial harvesting of krill, which could jeopardize not just their survival but also the critical ecological functions they perform. The findings from this research stress the necessity for further studies and integration of their roles in climate models, as their absence could considerably amplify atmospheric CO2 levels and temperature rises.

As researchers continue to study these fascinating creatures on expeditions aboard specialized research vessels, their work provides hope that understanding and conserving zooplankton will be critical in the fight against climate change. The study's results have been published in the renowned journal Limnology and Oceanography, demonstrating the ongoing importance of marine ecosystems in combating global warming.